Helen Lai and Chou Shu-yi’s First Collaboration:

The Dance Landscapes and Creative Reflections of Certain Movements and Shadows in Rehearsal

Text/ Professor Lin Ya-Tin

Associate Professor at the School of Dance, Taipei National University of the Arts

2 February 2025

Photo by Carmen SO

Prologue/Continuation?

At the end of 2024, I had the opportunity to visit Hong Kong—a trip since my last visit before the pandemic in 2019. During this visit, I arranged a time to watch Helen Lai and the dancers of CCDC rehearse their new production, Certain Movements and Shadows, scheduled to premiere in February. This production is a collaborative work co-choreographed by Taiwanese dancer Chou Shu-yi and Helen, invited by CCDC’s fourth Artistic Director, Yuri Ng.

The cross-regional connection between Shu-yi and Helen can be traced back to Winterreise · The Rite of Spring, which CCDC presented in the spring of 2019. This was a restaging of Helen’s earlier work, with the new version enriched by Shu-yi’s guest performance as Vaslav Nijinsky (1889–1950), the main character in The Rite of Spring. I had the privilege of watching the remarkable performance at Kwai Tsing Theatre in Hong Kong. When the production later toured Taipei Zhongshan Hall, I also conducted a pre-show talk for the Taiwanese audience.

Photo by Carmen SO

Verses from Bei Dao’s February: Unveiling the Premiere of the New Dance Work Certain Movements and Shadows this February

In this new production of Certain Movements and Shadows, Chou Shu-yi performs and co-choreographs with Helen Lai. Rather than dividing the choreography into separate segments, the two artists collaboratively developed the piece, drawing inspiration from the words of Chinese Misty poet Bei Dao (Zhao Zhenkai). Their creative process involved close discussions with composer Olivier Cong, stage designer Lee Chi Wai, and designers.

The title of the work is derived from the final line of Bei Dao’s poem February: “February in books/ certain movements certain shadows”. Originally a short dance piece premiered in 2006, it was one of Helen’s works that piqued Shu-yi’s curiosity. Although Helen was not satisfied with the earlier version, she recognised the vast potential within that poetic line. This led to the decision to retain the title while embarking on a new creative journey.

In May last year, Shu-yi returned to Hong Kong after five years to conduct a preliminary creative workshop, warming up and cultivating ideas for this production alongside Helen and the others. Within a week, Helen selected a series of Bei Dao’s poems for the team to read and discuss, serving as a foundation for their collaboration. Through recitations in different accents—Mandarin and Cantonese—they realised that, although all shared a Chinese heritage, their distinct urban backgrounds evoked diverse life experiences and emotional responses. Musician Olivier, with his keen sensitivity to sound, transformed the poems’ sentiments into sonic compositions. As for the dance movements, these were reserved for formal rehearsals in October, where the dancers explored how Bei Dao’s poetry inspired them, using these reflections as a starting point for choreographic design.

I recall watching the rehearsal in early December last year. The studio floor was scattered with sheets of white paper, some of it was relatively neat rectangular paper, but some of it was crumpled by hand. Stage designer Lee Chi Wai had even brought along a second-hand copy of Bei Dao’s Poetry with a gold cover. Having been soaked in water before, the pages had dried with undulating waves, giving the act of flipping through them an unexpectedly poignant feel. By chance, I flipped the page to February, the poem from which the title of this dance work is drawn. Here is the full text:

The night is rushing to perfection

I drift inside language

the musical instruments of death

are filled with ice

who sings on the crevice

of days, water turns bitter

flames hemorrhage

pouncing like pumas to the stars

there must be form

for there to be dreams

in the chill of early morning

a wide-awake bird

gets closer to the truth

while my poems and I

sink as one

February in books:

certain movements certain shadows

(Translated by Clayton Eshleman and Lucas Klein)

Bei Dao was born in China in 1949. In 1978, he co-founded the literary magazine Today. After leaving China in 1987, he lived abroad in Europe and North America before settling in Hong Kong in 2007, when he was invited to join the Chinese University of Hong Kong. This experience of drifting across places resonates with the themes that Chou Shu-yi and Helen Lai aim to explore through their dance work, delving into the intricate relationship between individuals and the cities they inhabit.

A Spark Rekindled Across Generations

In January this year, I had an online interview with Helen Lai and Chou Shu-yi, where we discussed their creative concepts. Chou Shu-yi shared his journey, having moved from northern Taiwan to Kaohsiung in the south, where he served as the curator of the Taiwan Dance Platform. Through his Boléro project, he travelled extensively across southern Taiwan, forging strong connections with the local dance communities. Toward the end of this project last year, Helen and Olivier flew to Taiwan to attend a performance. It was during this visit that I had the chance to meet Olivier, a talented young musician. Over dinner, he mentioned that his grandmother had once worked in Hong Kong’s film industry and had known Helen’s composer father. Remarkably, they even had an old photograph together as proof. This serendipitous connection, bridging different generations, beautifully illustrates how fate weaves its threads across time and space.

Last year, Shu-yi brought together a group of dancers from Singapore and Taiwan to present his work Dance a Dance From My Yellow Skin,[1] reflecting his recent focus on the relationship between the body and place. As he mentioned in our interview, “When the course of life carries us with the tide, where is home? Where is foreign land?” This contemplation of displacement and diaspora resonates deeply with Chinese communities—particularly the Chinese in Singapore, shaped by British colonial rule, and the Han people in Taiwan, influenced by Japanese colonisation. Coincidently, the lighting designer for Dance a Dance From My Yellow Skin was Lee Chi Wai, who is also responsible for the stage design of Certain Movements and Shadows. His lighting design played a pivotal role in the Weiwuying (National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts) version of Dance a Dance From My Yellow Skin, leaving a lasting impression with its striking stage effects. This group of artists, already attuned to each other’s creative rhythms, has come together again to collaborate on this new production. Through mutual refinement and imaginative exploration, they are sure to ignite sparks of brilliance—an artistic synergy well worth anticipating.

Photo by Carmen SO

CCDC Rehearsal in Early December Last Year

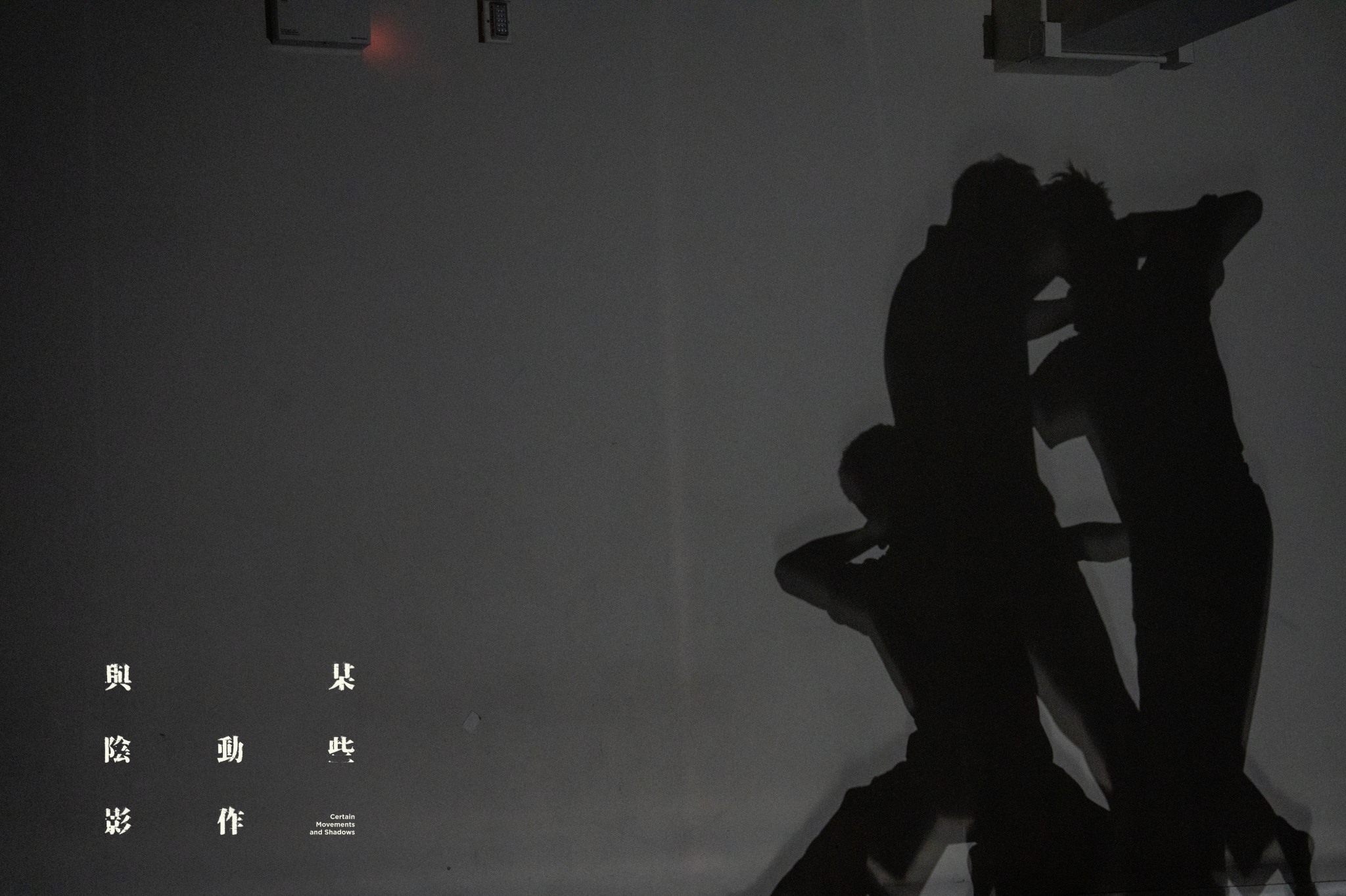

Although the rehearsal I attended last December featured only the ensemble section performed by the younger dancers, without the duet between veteran dancers Qiao Yang and Li De, and with Chou Shu-yi still occupied with the Taiwan Dance Platform in Kaohsiung, it was evident from the dancers’ rehearsal how they generated intriguing dynamics and movements through their interaction with the invisible words on blank sheets of paper.

Each dancers each explored a solo with sheets of paper. Among them, male dancer Simpsom Yau held a stack of papers close to his face, then let them fall, only to pick them up again from the floor, as if reading invisible words. His mouth opened slightly, as though on the verge of speaking, yet no sound emerged. In an instant, the atmosphere shifted. He seemed to waltz, but his facial expression quickly distorted into an angry, contorted state. He stuffed his foot into his mouth, and in the next moment, lay on his back amidst the scattered white sheets, tracing arcs along the floor with his limbs, resembling the motion of making a snow angel in the snow.

Another male dancer, An Tzu-huan, an Indigenous performer from Taiwan, presented a solo where he tightly clasped his hands over his eyes. As he slowly opened them, it seemed as if he could feel the gentle descent of snowflakes around him. Female dancer Nini Wang’s solo was equally dramatic—her intricate hand gestures framed her face, and in the quietness of the moment, even the subtle sounds made by her tongue were audible. Meanwhile, Skye Yao walked toward the audience from the centre of the rehearsal space, meeting their gaze directly as she recited an extended passage of poetry.

Since Olivier’s new composition was not yet complete at the time, Helen brought along tracks from Legend of the Seven Dreams (1988) by Norwegian jazz saxophonist Jan Garbarek to experiment with, pairing the evolving choreography with its evocative sounds.

The following day, over a meal with Helen, we discussed some of her stage imagery concepts for the piece. She mentioned her idea of placing hardcover books from her collection upright on the stage floor, having the book covers facing the audience. It is a symbolic invitation for them to step into the literary world within the pages. Perhaps this image was inspired by a line from Bei Dao’s poem Untitled: “… the books of mourning stand upright”.

Photo by Carmen SO

The Light and Shadows of Hong Kong’s Streets

For Chou Shu-yi, he is fascinated by the interplay of light and shadow within the text. In our interview, he shared a poem from Bei Dao that he deeply resonates with:

Outsider (translated by David Hinton)

“…the lifetime you’ve known

hiding in dark places

starts gaining attention

groping, hence light…”

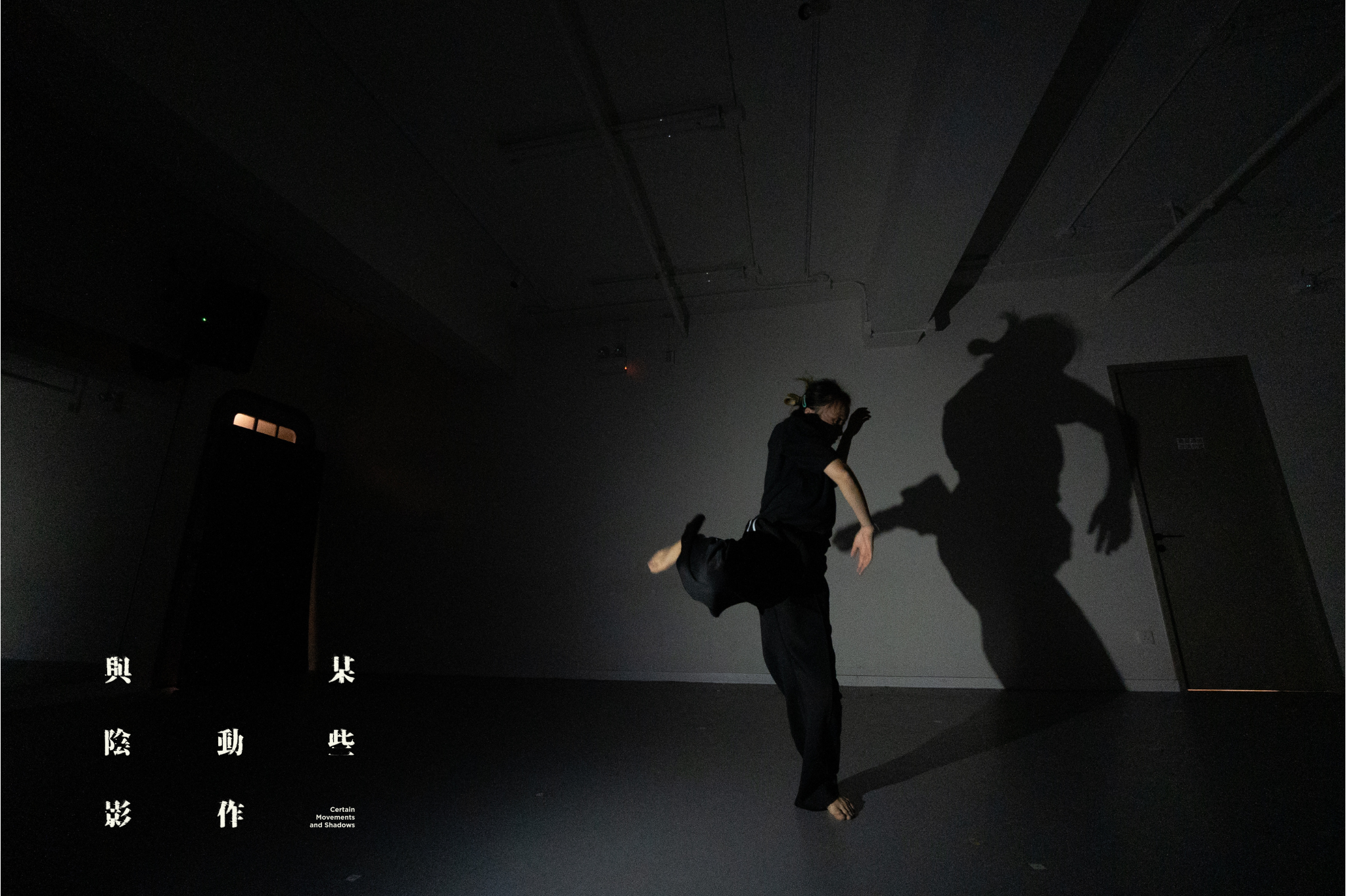

For Shu-yi, his role in the piece is closely tied to themes of solitude. He described feeling as though he were surrounded by piles of books, in a space that felt somewhat unreal. This sense of dislocation reminded him of a line from Bei Dao’s February: “… I drift inside language”. He experimented with dancing without a shadow. Out of curiosity, I asked how that was possible. He replied, “Either in complete darkness or in an entirely bright space!”—a metaphor for living in an era where nothing remains hidden. Yet, many things inevitably fade or transform over time. This idea is reflected in the work’s key visual: Shu-yi alone, casting an elongated, distorted shadow against the weathered white walls of Hong Kong’s Cattle Depot Artist Village. Concepts surrounding shadows were explored and refined in the rehearsal space through collaborative experiments with the company’s lighting designer, Law Man Wai. Shu-yi shared that he often drew the curtains during rehearsals to create total darkness. Sometimes, when Helen came in to observe, it was so dark that she could barely see anything!

Photo by LO Wing

A Landscape Built Together

As for the third member of the design team with the character “Wai (偉)” in his name, costume designer Wah Man Wai, what colour palette will he choose to shape the dancers’ stage presence? Will it also lean towards black, white, and grey tones? Helen added that she hopes the performers on stage will be seen as diverse individuals, each with a distinct personality. While their costumes may not rely on bright colours for contrast, the uniqueness of each dancer will shine through in subtler ways.

Will there be other projected visuals on stage, such as the Hong Kong street scenes featured in the promotional video? The two choreographers revealed that while there might be some, the production will not rely heavily on concrete visual imagery. Instead, projections will focus on books, paper, and text, allowing the audience greater freedom for interpretation. Olivier will perform live on stage with various instruments, adding layers to the performance.

For this production, Shu-yi co-choreographs and performs on stage, juggling multiple roles—a demanding endeavour. At one point, he even exclaimed in French, “Je suis fatigué” (“I’m tired!”), to which Helen playfully added, “très” (“very”), turning it into “Je suis très fatigué” (“I’m very tired!”). Shu-yi, respectfully referring to Helen as Professor Lai, was teasing each other, showing that the two of them are very close friends.[2]

A New Beginning for CCDC in the Year of the Snake

It’s worth noting that during the performance week, CCDC will host a special talk at the Hong Kong Arts Centre titled Capturing the Essence in Dance Performance: How to Archive and Record. Centred around Helen Lai, the event will feature three guest speakers who will explore approaches to preserving dance through oral history, dance videography, and digital archiving, sharing insights on how different documentation methods help keep works alive for future generations.

As CCDC welcomes its fifth Artistic Director, Sang Jijia, this year, we look forward to seeing new energy infused into this 45-year-old company as it embarks on its next milestone.[3]

1. Reference: Chen Pin-hsiu’s dance review, “A Boat Gently Rocks on the Lake of My Heart — Chou Shu-yi’s Dance a Dance From My Yellow Skin,” * published on ARTalks, Taishin Arts Review Platform. 2024/5/9. https://talks.taishinart.org.tw/members/224/38550.

2. Helen Lai, recipient of an Honorary Doctorate from The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 2021. https://www.hkapa.edu/tch/honorary-awardee/doctorate/helen-lai-HD

3. City Contemporary Dance Company Appoints Sang Jijia as Its Fifth Artistic Director. https://www.ccdc.com.hk/2024/11/22/ccdc_new_artistic_director_sangjijia/